LATEST TRAVEL

British Columbia’s major ski resorts close to the US border are world-class in every sense. High-speed lifts, fine dining, bubbly spas waiting at the hotel. On the other hand, the ski towns of Northern British Columbia — known to locals simply as “The North” — are noticeably, and intentionally, not like that at all.

In The North, you’re more likely to ride a T-bar than a six-pack chairlift. And $15 cocktails? Only if you order a double. What you will find is North America’s most community-driven ski scene, a collection of small towns, and hand-crafted ski areas free of the continued conglomeration enveloping the resorts further south. The Kootenays may have the Powder Highway, but The North has Highway 16.

Highway 16 — the Highway of Legendary Stoke

Photo: GROGL/Shutterstock

Highway 16 connects the towns of Smithers and Terrace. It’s a span of just 126 miles but accesses a lifetime of ski exploration. Smithers is a community of barely 5,000 residents set amongst the jagged peaks of the Hazelton Mountains that rise high above treeline. It’s the hub of skiing in The North, offering easy access to designated backcountry terrain and small community ski areas.

Smithers is a 13-hour drive north of Vancouver, but you’re better off taking a 90-minute flight from Vancouver International Airport. At the other end of Highway 16, or a two-plus-hour drive west, lies Terrace, home to 16,000 residents and its own airport connecting with Vancouver.

“We are surrounded by amazing terrain that is relatively easy to access if you’re willing to put in a bit of work,” says Dave Walters, co-owner of the Local Supply Co. gear shop in Smithers. “It’s always worth the effort. Very seldom we aren’t able to find untracked turns.”

Here, above the 56th parallel, the slopes are as empty as an elementary classroom during recess. The ski areas offer inbounds and backcountry, with clearly marked runs that make lapping a day in the “side country” nearly as easy to navigate as the lift-accessed runs — though you’d better come prepared to earn those face shots.

A scene hand-built by the communities that ski here

Nearly every skiable spot here developed in the same way: A group of local skiers and boarders came up in the summer to make runs. A community formed around those runs, with local sponsors financing maintenance and volunteers performing upkeep by hand. The surrounding community embraces the effort, protecting the land so that both locals and visitors can enjoy what it offers. No big dollar investors, and no excuse to sit in the lodge all day. Bring normal ski or snowboard gear, plus backcountry touring equipment that includes a beacon, shovel, and probe. Touring poles and a winter-specific backpack are necessities as well — along with enough Clif Bars to feed a small army.

Hankin Evelyn — the first backcountry-only ski area

Photo: Tim Wenger

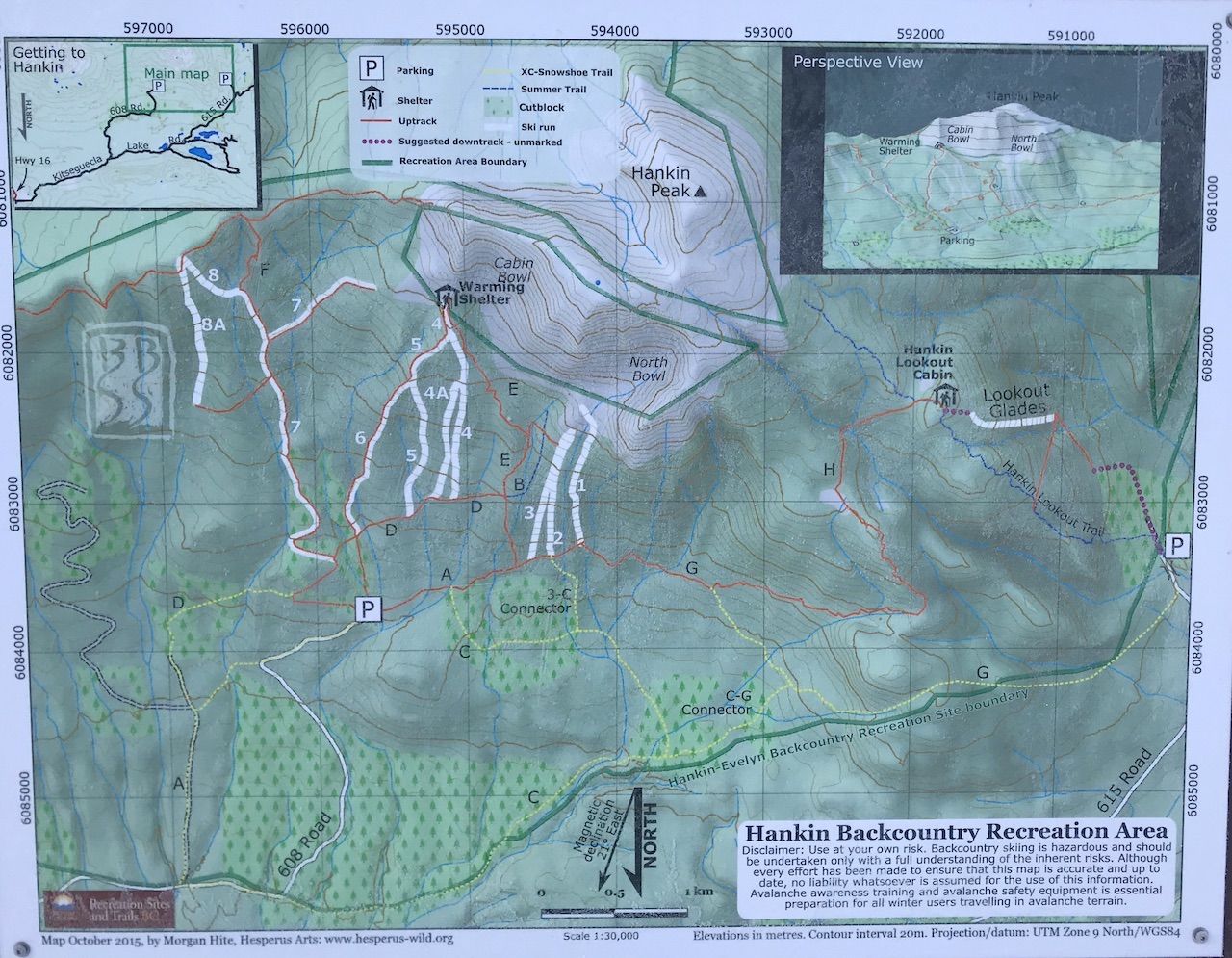

North America’s first lift-free and lift-ticket-free ski area, Hankin Evelyn Backcountry Recreation Area sits about 30 minutes north Smithers. The trailhead is a few miles up a bumpy four-wheel-drive road off the highway that dead-ends at the parking lot. You’ll see runs cut into Hankin Peak and a few on neighboring Evelyn as you approach, but that’s about all you’ll find as far as development.

The area is the brainchild of local skier Brian Hall, who brought to life this idea of a backcountry zone where skiers and boarders could familiarize themselves with backcountry best practices and gear use in a lower-risk setting, skinning up to a hut and skiing runs cut into the forest below. Once comfortable on the 13 cut runs, Hall’s thinking went, they could then make their way into the high alpine terrain up above the hut.

The area officially debuted in 2010 and was immediately embraced by the community. During the offseason, local fire crews and forestry workers help to maintain the runs and ski touring routes. It’s all done on a volunteer basis, with donations assisting a local farmer whose land you’ll cross over on the access road to the parking lot. Hall’s work has since spawned the Bulkley Backcountry Ski Society, a local organization working not only to map and maintain local backcountry ski zones but to educate the public on how to safely access them.

Photo: Tim Wenger

An uptrack is established from the parking area to a day-hut just below the treeline. The ascent on skins is steep at points but frequent switchbacks ease the burden. The hut awaits about 1.5 hours up the trail, a solid place to recoup over a snack while looking at conditions to decide how much further to ascend and, ultimately, which runs to lap. If conditions allow, an additional 20-minute push up from the lodge takes you about halfway up the Hankin Peak bowl, the summit of which is generally not safe to ride until late March at the earliest. The best out-run to avoid a wicked traverse is Run 4A down from the hut at the end of the day. There is an old fire cabin that rents out overnight for a moderate fee. Beyond that, the entirety of Hankin Evelyn is free to access.

Hudson Bay Mountain — keeping it old school

Most ski resorts don’t even have T-bar lifts anymore, let alone use one as the primary lift access from the base lodge. Hudson Bay Mountain, just outside of Smithers, keeps it old school. Hop the Panorama T-bar to access 1,750 feet of intermediate and challenging in-bounds vertical, but bring your touring gear because the best powder is found out of bounds. The Ozone area, a section of backcountry terrain accessed via a quick traverse from the top of the main T-bar, is made up of about eight defined runs maintained by local volunteers from Smithers. Runs are informally named after the “borrowed” street signs posted on trees near the drop-in points, so you’ll find yourself heading both up and down trails called “Handicap Access” or “Parallel Parking.” (The signs are also a worthy photo stop.)

After traversing from the Panorama T-bar on the Skyline Connector run, pass through the Ozone gates and work your way across to the drop-in points for these runs. Signs are not readily available, so ski with a local who knows the area. Drop in wherever you feel pulled to a particular line, and cut right upon reaching the Ice Fall Traverse, which spits you out near the bottom of the Skyline Lift. You can also skin back up from the traverse, getting in a half-hour of cardio while avoiding the lift ride. A couple of small signs note the traverse. If you miss it, you’ll end up on the Rotary Club Trail To Town, a 2.6-mile run from the base of the Skyline Lift down into Smithers.

Stop for lunch at Whiskey Jack’s Pub in the lodge and enjoy a burger while taking in views of the surrounding Hazelton Mountains. To really get the community vibe in full, take the Trail To Town — easily the area’s most unique feature — back to Smithers at the end of your day. Or, start your day (or evening) with a challenging 90-minute skin up from the trailhead to the Skyline Lift. No lift ticket is needed to access this trail, and it’s two-directional.

“A lot of people will get off work in the afternoon, strap on their skins, and make it as far up the trail as they can before dark,” says Walters. “Then they’ll ride back to town in time for happy hour.”

Shames Mountain — a community-owned ski hill

Twenty minutes from downtown Terrace, Shames Mountain is an incredible story of a community coming together to save its ski hill. When the nearly 2,000-acre ski area was built in the early 1990s, it was slated to be the “next big thing,” but the private owners who cut runs into the hill and put in a chairlift and t-bar quickly ran into financial troubles. It simply wasn’t accessible enough to attract the hordes of skiers visiting the bigger resorts closer to the American border.

“The private owners thought they had a Whistler concept,” says Christian Theberge, General Manager of My Mountain Coop, which now operates the ski area. “They made a lot of good infrastructure decisions, but the population just isn’t here and they lost a lot of money.”

The community rallied for a solution, and a non-profit group called Friends of Shames was created. Through grant-funded feasibility studies, the group concluded that a member-owner co-op structure would allow the hill to remain open, financed by grants and corporate donations in addition to its member-owners. The question then became raising the funds. Would local residents actually be interested in buying a share of their ski hill?

It turns out they were interested, and today there are more than 1,500 local shareholders. The co-op has also purchased new equipment including snowcats, investing more than three million Canadian dollars ($2.25 million) into mountain infrastructure. On any given day, nearly half the people skiing the mountain actually own a piece of its operation. Many of the remaining skiers are school groups and expert-level skiers and snowboarders drawn by the resort’s steep pitch, ample powder, and easy access to backcountry touring terrain.

“When I got here, we were doing 18,000 ski visits per year,” says Theberge. “This year we’re on pace to do 30,000… Our focus has been our local market, but our destination market comes for the backcountry terrain.”

Photo: Tim Wenger

That terrain is among the best resort-accessed backcountry in North America, with over 7,000 acres in 26 distinct touring zones. Backcountry Skiing Canada has compiled detailed trail maps and zone information, including access points and info on difficulty. Most tours take skiers above treeline and lead down through thick forest to a drainage runout, eventually funneling back towards the ski area or highway. The easiest to access is the Mystic Valley Trees, requiring about an hour of touring to reach. Other zones like East Ridge and Fay-zurs are full-day trips in themselves, taking at least four hours to skin to, plus descent and exit time. The lodge rents all necessary backcountry gear in case you didn’t bring it with you.

Whether you tour or stay inbounds, be ready for deep. Due to its coastal location, the mountain routinely receives more than a foot of snow per storm and averages 475 inches of snowfall annually. Fortunately, the runs are steep, often sending skiers bouncing down pillow lines made entirely of snow from the most recent storm.

When backcountry conditions aren’t safe, stick inbounds on runs like Hangover and AOT, skier’s right from the top of the Red T-bar. The trees here after a big snow are like navigating a tight canyon in a kayak. Lean in and flow with the terrain, letting it guide you across the curves of the mountain and between the trees. By February, enough snow accumulates here that many tree bottoms are encased in a mound of blue ice that reflects the branches’ frosted white tips. As beautiful as it is, keep your eyes focused downhill because one wrong turn and you’re headfirst into a mound of soft powder.

“You have to make good route choices, that’s for sure,” says Theberge. “You have to be good on your feet to handle 30-40 centimeters of snow, and we get that commonly.”

Other backcountry access points and local tricks of the trade

If your crew is ready to hit unmarked terrain, you have a few options. Skeena Cat Skiing accesses chunks of a 148,000-square-acre area north of Smithers and has overnight tent lodging at Gail Ridge ski area. For a swankier, all-inclusive experience, Skeena Heli-Skiing operates out of the Bear Claw Lodge, set on the bank of the Kispiox River about two hours north of Smithers.

Anywhere you venture out of bounds, always follow backcountry best practices. “Avalanches here are low frequency but high impact,” Walters says. Before heading out in the morning, check Avalanche Canada for up-to-date conditions. As with any backcountry terrain, always carry a beacon, shovel, and probe, and never ride alone. There’s a lot of open wilderness, and it could take search and rescue quite a while to find you should something happen. Because cell service isn’t guaranteed up here, your best bet for on-mountain communication is to give everyone in your group a walkie-talkie. To be prepared in case of an emergency; at least one person in your party should have a Bivy Stick or similar satellite transmitting service.

The towns have you covered for gear, rentals, and aprés. Any gear you don’t bring with you can be found at Local Supply Co. in Smithers, a fully stocked retailer that blends the best of both a local skate/snow shop and a full-service REI store. “In our store we see firsthand the growing interest in backcountry skiing and splitboarding,” Walters says. “As that community grows, newer areas are developed, and we all benefit from that.”

After a full day of skiing, gather at Smithers Brewing Company for aprés before grabbing dinner at Telly’s Grill or the Roadhouse. Terrace has a similar post-ski circuit, with a happy hour pint at Sherwood Mountain Brewing often leading into more revelry at the Skeena Bar & Social House or Don Diego’s downtown. ![]()

The post Independent, low-tech ski areas are the draw in Northern British Columbia appeared first on Matador Network.

from Matador Network https://ift.tt/2VB07Xj

No comments